Module 12

Extended Western Theory and Techniques; Is Jazz still a Thing?

It is…

Jazz has an incredibly unique relationship within the history of the United States. In its conception, it is the first major development of any popular/folk genre seen in the United States, stemming from the development of African-American spirituals in the early 1900s. By the mid-20th century, jazz served as the progenitor to many new genres of music including rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and country music - all of these subsisting into their modern counterparts. Today, jazz has found itself as a mainstay in the halls of academia, becoming the only other major genre aside from western classical music to do so. In this module, we’ll be taking a look at the recent developments in jazz music, the divisive issues that arise because of this and using the medium to analyze some advanced western theory concepts. But first, as always, a little bit of context in jazz history.

A (very breif) history of jazz

As I’ve alluded to in several modules before this one, the roots of jazz can be traced all the way back to the late 1800s. Though African-American musical styles and traditions extend several centuries before that, the musical style known as ragtime would be codified through the turn of the 1900s and set a path for the development of jazz. The capital of ragtime is often claimed by St. Louis, Missouri, but other hot spots for the style include Mississippi and Louisiana. As a style, ragtime features heavily syncopated rhythmic ideas that often incorporate some form of polyrhythmic action (if you’ll remember these terms from Module 7). The genre began almost exclusively with solo piano works, but subsequent revivals across the decades would see the style incorporated into other common jazz band instrumentations¹. Perhaps the most well-known rag composer would be Scott Joplin - with two of his most well-known compositions here to the right here.

By the 1920s, ragtime was falling out of style and the era of the big band was in, with notable scenes in New Orleans, Chicago, and New York. While early iterations of the genre may be better described as ‘small’ bands, they generally featured some combination of saxophones, trombones, and trumpets, and rhythm sections featuring a piano, bass, drumset, and sometimes a guitar. During the height of its popularity in the 30s and 40s, these bands would feature upwards of 15-20 people, with additional instruments added depending on the tune, such as different horns or vocals. A common and popular organization of this big band ensembles would consist of individual composers or performers taking on the position of band leader while featuring a definite or rotating set of musicians that made up the band or orchestra². Most notably, out of the big band instrumentation came a style that would go on to exemplify jazz for the next century, swing.

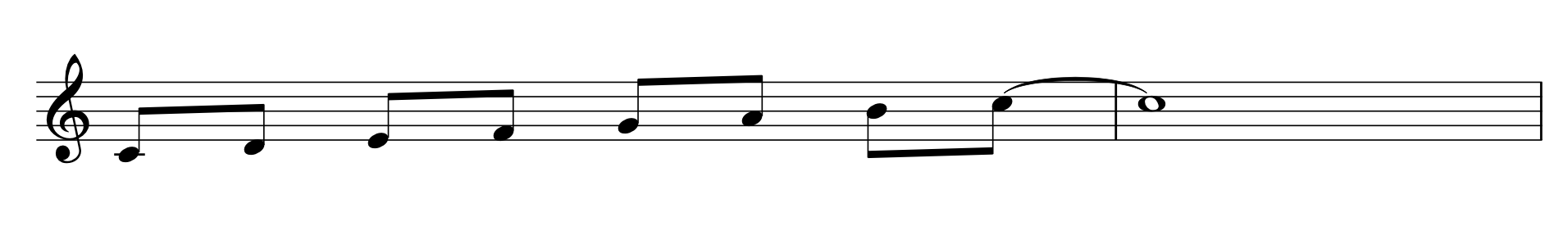

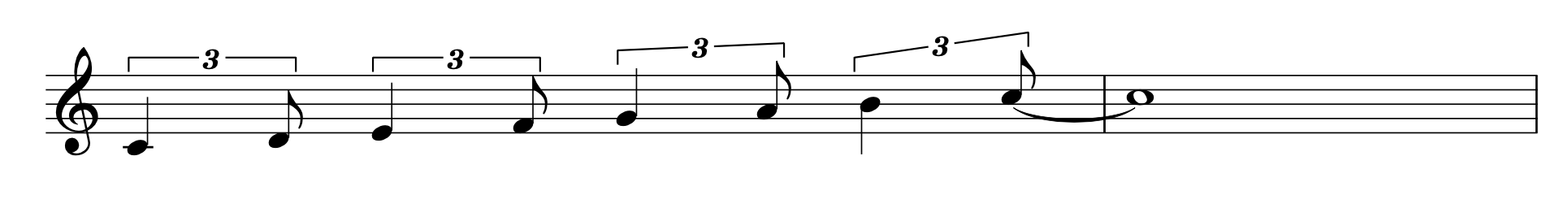

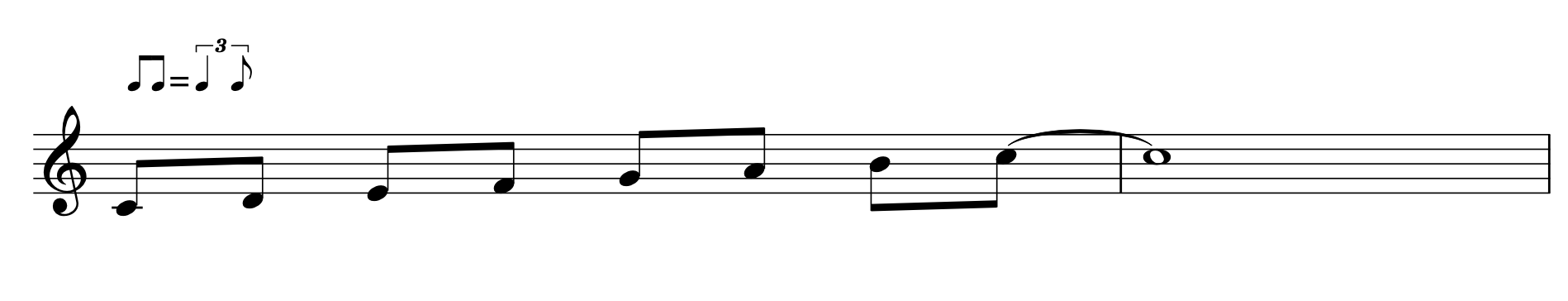

In music, swing is a specific technical aspect as well as a genre moniker - defined for and by each other. In notation, swing can be shown as a proportion of triplet rhythms, see and hear the examples to the right here. The first example is of non-swing eighth notes, colloquially referred to as ‘straight’ rhythms. The second example demonstrates what would technically be notated as swing rhythms, with some weight, emphasis, and length added to the first note of every eighth note pair. However, early jazz musicians would rarely use modern, western notation in performances, so the swinging rhythm would be inferred depending on the song, style, or band playing. For modern ensembles, the last example would be what is seen, straight eighth notes but with the direction to swing them - also shown by simply indicating with the word “swing.”

In retrospect, a couple of the most popular bandleaders from this era include Duke Ellington and Count (William) Basie, though keep in mind that there are so many more where that came from. At this same time, there were many notable female singers who were coming up in the performance of these kinds of ensembles as well, such as Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. Notable on one hand for distilling a completely new genre/style of singing found in vocal jazz, but also notable for the breakthrough in an incredibly male-dominated field. Check out some examples of these folks in the following examples!

Starting in the late 40s and through the 50s, jazz saw a few more major developments in style and character. Coming in first was bebop, sometimes just called bop. Musicians practicing bebop would often take old, common compositions (referred to as standards) and recontextualize them in new, and complex ways, both harmonically and rhythmically. New harmonic extensions and extended playing techniques were common, with the virtuosic and improvisatory playing of soloists being brought to the forefront. On the other side of this spectrum and perhaps in response to bebop was the development of cool. This genre scaled back the bombastic influence of bebop into a less intense and “more thoughtful” approach to performance. Check out the differences between these two genres with Charlie Parker (bebop) and Miles Davis (cool) to the right here.

From the 60s and on, jazz would continue to develop around other popular musical traditions at the time. Some examples include avant-garde jazz (often referred to as free jazz) derived from the avant-garde art movement, as well as soul & funk with heavy influences from rock and R&B. As with the other forms of popular music we’ve studied so far, genre begets sub-genre begets sub-genre in the exponential growth of musical styles as we approach the 21st century. Around this time we also start seeing the broader genre of jazz being incorporated more and more into academia. This well-intentioned elevation of a popular genre seemed to make sense from the perspective of capital and academic vigor but may have inadvertently frozen the genre in an overly-academic stasis - much like classical music has been for the past century. Though, as we’ll see in the next few examples, jazz - or some form of it - is continuing to evolve and thrive in plenty of places.

Before moving on, though, check out this stylized chart developed by Portia Maultsby. In it, you can see the distinct lines between many of the popular genres we’ve talked about throughout the course!

Segue

As we begin looking at some modern jazz, we are going to take some time to identify the theoretical elements that can help us better understand the music. As happens to be the case with jazz, we are going to be looking at some pretty complicated music. So, instead of focusing on the minutiae of these theoretical elements, we will opt for a fly-over approach to distill a broad understanding as we cover some great artists in the field today. In any case, let’s move forward!

Formal Elements of Jazz and Improvisation

When talking about form in music, academics will use relatively standardized systems to show comparable and contrasting sections of music, as well as how those sections are based. While by no means standardized, the system we first learned at the beginning of this course can also be used to analyze the form of a piece. Everything from intros, outros, and choruses can be found in jazz tunes, but there are some more terms and common tropes that can be found in common across many pieces in the genre.

Let’s start by listening to this tune by Jazzmeia Horn, Free Your Mind. As you’re listening, you’ll hear a repeated, extended chord progression that makes up the chorus of the song. These series of repeated choruses make up the bulk of many kinds of standard jazz tunes and provide room for performers to improvise. Improvisation has been a key element of jazz since near the time of its birth and consists of performers composing in real-time against a set arrangement or chord progression. This kind of real-time composition allows for (almost necessitates) a certain push and pull with the performers as they improvise against one another. In this piece, sections of improvisations are provided to the vocalist (Jazzmeia), the pianist, and the bassist during the chorus, and again Jazzmeia during the outro.

Let’s look at another example, Kamasi Washington’s (saxophone) Street Fighter Mas. The piece plays out like a standard tune, with an intro, a bunch of choruses with improvisations, and an outro. In this piece, the intro lasts about 28 seconds, with the first chorus starting with the singers coming in. Let’s break down these choruses now.

The first iteration of a chorus in this context is called the head. The head features pre-composed music that will serve as the basis of the future choruses which are improvised over, often including the full band’s instrumentation and the main melody if it has one. Following the head are the turns of improvisation (sometimes referred to as middle-choruses), often taking the form of an extended or several repeated choruses. In this piece, the trombonist is the first improviser, followed by a repeat of the head, and finally an extra-long chorus for piano improvisations. Once improvisations are finished, the band will often play the chorus in one final iteration called the out-head, again bringing back full instrumentation. This can lead to the end of the tune, or a proper outro that differs from the last chorus in some way.

Let’s now listen to one more piece in this section, Last Chieftain by Christian Scott. This parred-down instrumentation allows us to better analyze the qualities that are going into the improvisations, particularly between Lawrence Fields (piano) and Elena Pinderhughes (flute). The two engage in consistent interplay throughout the improvisations, starting at about 2:30 in the video provided.

Generically, this could be labeled some kind of call and response. Call and response is a consistent element across American music derived, again, from West/Sub-Sarahan Africa. It features the presentation of a musical idea that is then responded to in turn with another idea. We may be most familiar with this form in children’s songs we learned growing up. Though, when practiced between two professional musicians, simple call and response turn into an incredibly intricate dialogue between them. At the beginning of the flute improvisations, Elene is providing a soft melodic line which Lawrence responds to in kind with soft articulations and smaller melodic fragments that compliment the flute melody. As the improvisations continue, energy and tension are built up between the two as their rhythms become faster and more erratic, perhaps clashing with each other at times. This culminates in the song’s musical climax as the two are in full virtuoso mode - with the call and response evolving into a full duet. While this is only a casual pass at describing the interplay happening here, thinking about improvisation segments in this way can be a way to guide you’re listening to relatively complicated music! Speaking of which…

Extended Harmony & Metric Madness

As promised not to get into the nitty-gritty of extended jazz harmony, otherwise this lesson will never end. Instead, let’s begin by identifying some of the broad components found in modern jazz fusion bands.

Starting with SLIP by Shubh Saran, we have a different exploration of rhythm and form compared to our previous listenings. The piece features almost exclusively a soloistic interplay between all members of the band as opposed to choruses dedicated to a single player, though still containing quite a bit of improvisation. Though, with highly rehearsed and professional players, the piece sounds as if it was through-composed with distinct sections, again, unlike the standard chorus structure we’ve since listened to.

In meter, the band sets up an intricate polyrhythmic groove. A groove in music has many meanings, but can generally be used to refer to regular (i.e. repeating) patterns. And if you will remember, polyrhythms are two regular rhythmic ideas that are played against each other at the same time. In this case, during the choruses, Shubh implies an alternating meter of 4 and 5 quarter notes with his guitar riff while the percussionists instead imply an alternating 7/8/9 eighth note meter, creating various polyrhythmic relations like 4 against 7, 5 against 8, and 4 against 9 - or as far as I can tell, it is incredibly complicated after all! Pair these moments with the sudden shifts in tempo and meter across the song and you get quite a musical mess. Though, with the establishment and practice of a groove that ties everything together, the musicians are able to perform together with relative ease!

Let’s now turn our attention to some harmonic discussions with Snarky Puppy’s Lingus. The piece is down-tempo compared to the previous, playing at first like an R&B ballad before evolving into a high octane closer. Like before, the song features several solos, including an extended one from the synthesizer by Cory Henry, starting at about 4:25.

As for pitch and harmony, the piece features a series of chord progressions with uncommon interval structures and extensions. When we’ve talked about chords before, I’ve almost always presented them as a series of 3rd intervals. But why not build chords with different sized intervals. In fact, that seems to be the case during the beginning choruses of the piece, where harmonies are built on 4th’s and 5th’s instead, creating quartal and quintal harmonies respectively. Upon first listening, this gives us a completely new sound ideal that we may not be familiar with when compared to other pop tunes we’re familiar with.

Extensions are another way to alter the way we use chords. Up until now, I’ve mostly only presented triads, notes of 3 chords, but we can just as easily use more than that! These are generally referred to as extensions, as we add chords onto existing triads that have an established function. Common extensions may be the inclusion of the 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th interval of a chord - a continuation of stacking thirds. These extensions can also be altered to create intricate and new harmonic functions for a chord, and imply new pitch structures to be used over the top of them when improvising. This is as clear as can be when listening to the synth solo by Cory in this piece, where he provides these altered chords in one hand while creating new melodic material in the other. And to reiterate - at this I don’t expect you to follow along with these pieces and understand the harmonic or rhythmic intricacies, but rather to give you an idea of the kind of content that is informing these performers and their performances.

Learning Extension: Popular Fusion

For this extension, I just want to leave you with a little bit more listening. Below are a couple of pieces by hip-hop/pop artists Kendrick Lamar and Lizzo. Both artists have music that is heavily influenced by the style and performance practice of jazz in one way or another. As you’re listening, see what you can pick out including instrumentation, sampling, style, harmony, and rhythm.

Module Assignment 12

Critical Listening: Jazz Style and Form

Listening to The Fisherman by NÉJIRA, see if you can correctly identify the different styles and formal elements that make up the song.

(Click the ‘Module Assignment’ link for a quick way to the assignment)