Module 3

Melody, Harmony, and Meter; Looking at Pop Across the World

Three components inherent to nearly every style of music…

No matter what way you define the terms, music styles from across the world will feature some combination of these components; melody, harmony, and meter. It may be evident without saying so, but I want to make it clear that music is by no means a science. You do not specifically need all three of these components present at all times for something to be considered “music.” For the purposes of analyzing these pieces, however, breaking down music into some broad components helps us begin the task of analyzing music. In fact, when you begin to move past the basic components that help us describe most music, you can begin finding some great pieces that lack all but one of these components!

Anyways, let’s begin this module by looking at the first component - melody.

Building Melodies

Like most terms we come across, melody can be defined in a myriad of ways. The dictionary nerds at Merriam-Webster define melody as “a sweet or agreeable succession or arrangement of sounds.” Meanwhile, music nerds will define a melody within the context of a piece of music, using a more descriptive approach. However, most people will colloquially refer to a melody as the main tune of a piece of music. We will mostly be using the last definition for our uses in this module, but we will also be working to develop a more critical understanding of how melodies are created and the purpose they serve in music. First, let’s look at the physical content of melodies.

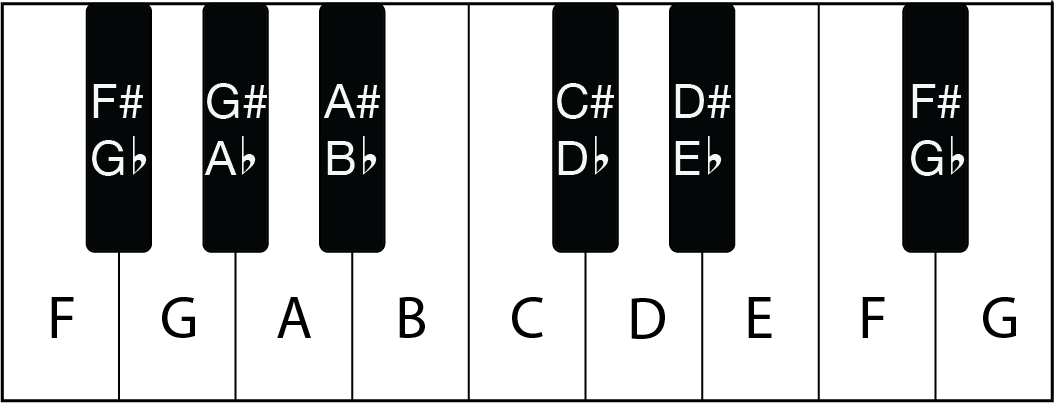

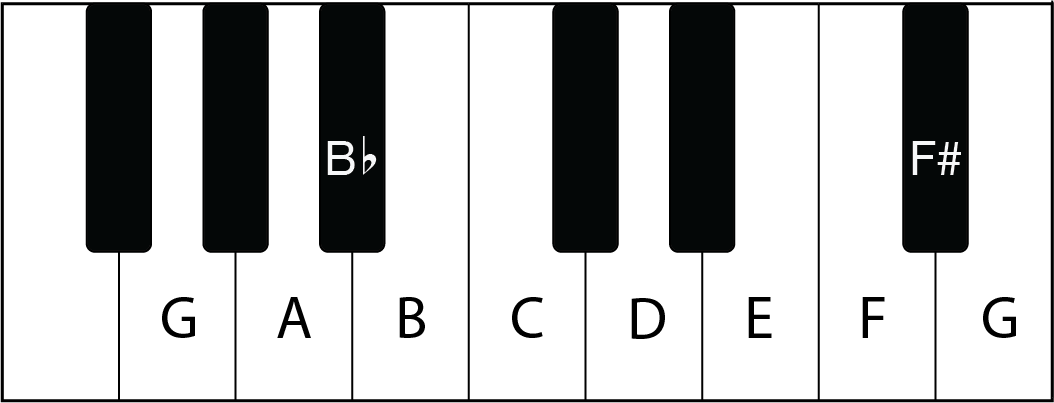

On a keyboard, each white and black key is associated with a pitch. In western-music, we have 12 distinct pitches before they start repeating at the octave

If you will remember, we described pitch in the first module as how high or low a sound is perceived, and also that these pitches can be strung together to create melodies. As a way to organize these pitches, we can organize them by their aural characteristics into pitch collections. Pitch collections are exactly what they sound like - a collection of pitches. By far the most common way to form a collection of pitches is through diatonic tonal areas or keys. If you’ve ever performed in a music ensemble in college or high school, you’ll at least have a passing knowledge of what I’m referring to. Don’t worry if not, though, we’ll still cover it! To begin, you’ll want to be familiar with pitch letter names, as shown here on this keyboard.

Diatonic melodies are created using a fixed-pitch collection that is based on a single note, also called the tonic. The tonic of a pitch collection can be described as a reference point or “home-base,” and is defined by its function and relationship with other pitches within the collection. To find the pitches within diatonic pitch collections, you can build scales off of the tonic using a specific pattern of pitch distances. By changing the patterns, you change the pitch collection and subsequently the sound. In western music, each pitch is considered to have a function, or a tendency to lead to other notes. For example, the fifth and seventh note of a scale has a dominant function, meaning it has the tendency to resolve to the first note of the scale, the tonic. These tendencies can be used or subverted depending on the context in which they’re used.

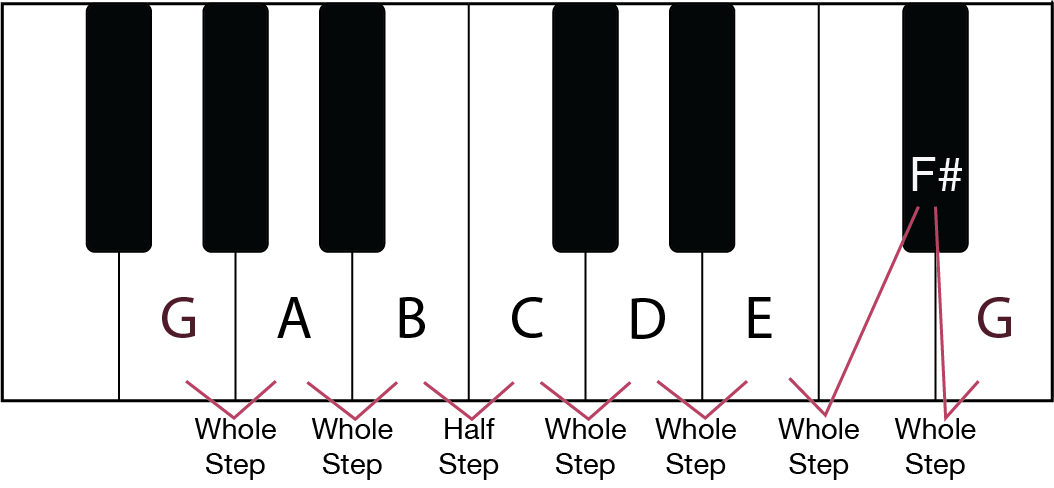

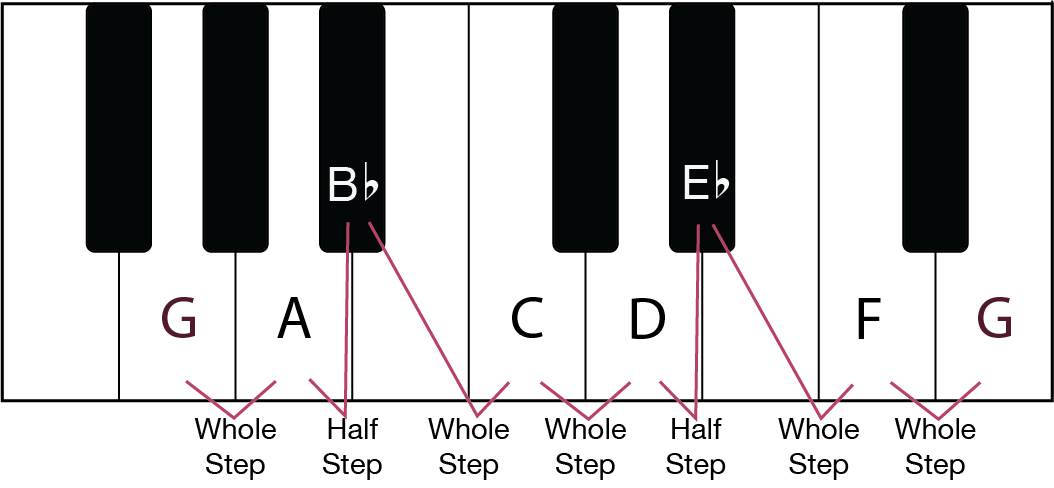

You can see the diagrams of two very common patterns that create the major and minor modes below. These two modes make up a significant portion of the music created today. They consist of a series of half steps and whole steps that, when starting at the tonic of G, create their respective modes of G major and G minor. These patterns can be applied to any pitch letter, and this creates these modes with different tonics. Check out the files below to hear these scales played sequentially.

The G major pitch collection, found by applying the known pattern to the tonic note G.

The G minor pitch collection, found by applying the known pattern to the tonic note G.

Altered, mixed or chromatic melodies use the diatonic scales we’ve just learned and alter them in some way. As you can imagine, altering the pitch collection will bring new opportunities and functional possibilities. The term mixed comes from the combination of two different kinds of pitch collections that share some notes and thus sharing some functions. The term chromatic is an old term that stems literally from the Greek word chroma because the altered pitches have historically been perceived as creating a more “colorful” collection.

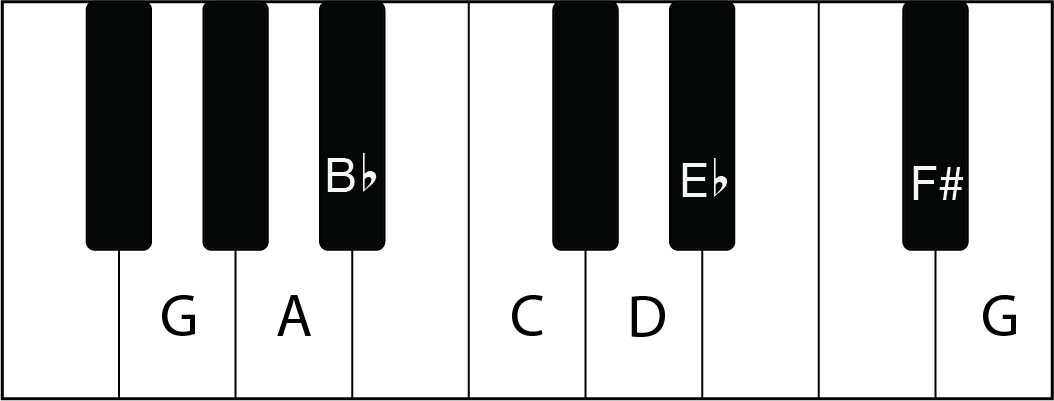

One of the most common alterations comes from the minor scale, where the seventh note of the scale is raised to provide the dominant function found in the major scale. This may not seem like much right now, but when a melody features this dominant function and is supported by an underlying harmony, it creates a very pleasing resolution common in pop music - more on that in a bit. A common mixed pitch collection can be found in the blues scale used extensively in jazz genres and even some pop music. It combines the pitches of the diatonic major scale and the diatonic dorian scale, dorian being just another mode, like major and minor. Check out both of these collections below on both the piano and the audio files.

G harmonic minor, which raises the seventh note of the scale minor scale from F natural to F#.

A 9-note blues scale on G, borrowing the notes B♭ and F natural from the dorian mode.

Note that despite all of the academic-sounding explanations of the above terms, our perception of diatonic and chromatic relationships is completely arbitrary. The only reason you are able to ‘feel’ these relationships in the way I described is because of the cultural supremacy of western-music for the past several centuries and the continued practice of it today. While some western-music purists may try to justify this supremacy with acoustics/sound science, there is no scientific explanation for why we perceive these relationships as ‘pleasing.’ These justifications are further invalidated with modern approaches to pitch perception and composing, but also in the use on non-western functions in use across the world for centuries.

Other constructions of pitches do exist. For example, non-western melodies that utilize different temperaments have been used for centuries to make music in Eastern Asia. Classical Arabic and Indian music feature microtonal pitch inflections regularly - microtonal meaning a pitch interval smaller than the smallest interval in western structures, the half step. These microtonal pitch expressions are actually used all the time in the pop music we’re familiar with through vocal inflections, electronic processing, or bending the pitch of an instrument such as a guitar. In other instances, the 12-tone temperament will be used, but the function of the pitches will differ from what we’re used to. Further still, contemporary musicians are experimenting with new pitch temperaments all the time, with lo-fi hip-hop being a popular one that comes to mind. All of this to say that the world of pitch is not set in stone, and maintaining a broad perspective of this component will ultimately better serve your experiences with music in the future.

Extrapolating Harmonies

I also mentioned that pitches can be combined with one another to create harmonies. Melody and harmony are inextricably linked to one another within music, and while a piece of music can technically exist without one of these components, they each imply and inform our perceptions about each other. For example, a songwriter will first take the poetry for their new song and sing a melody to it. The songwriter, assuming they’re writing their own music, can then take the notes of this melody, and find other notes that support this melody. The opposite could also be true, where a songwriter takes a series of chords they like, and then sing a melody that “fits” over it. Chords are simply multiple notes sounded at the same time and are intended to be perceived together.

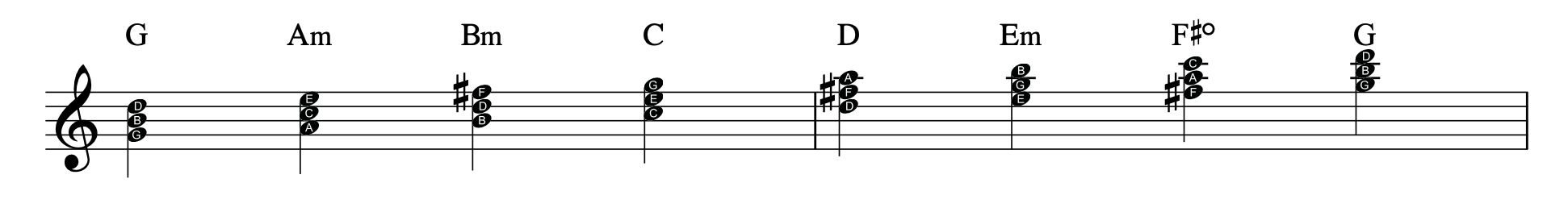

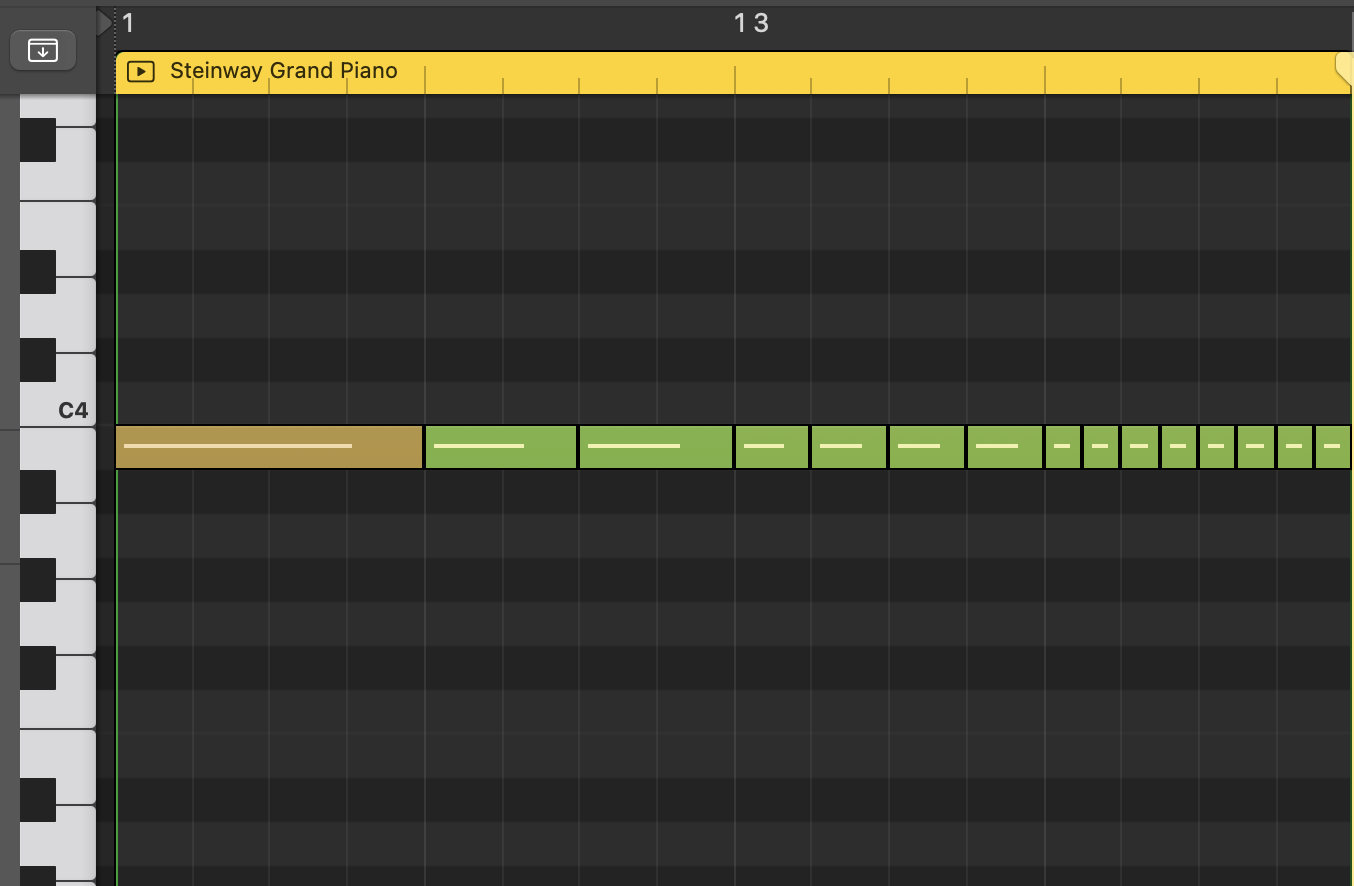

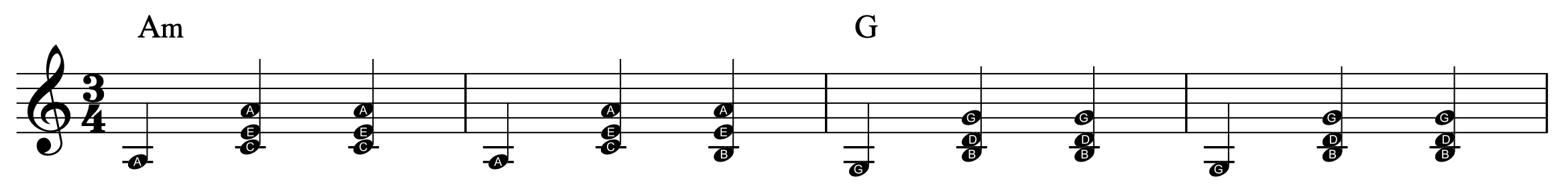

How does a musician choose what chords to use in their song, though? Well, most of the pitches are already chosen for them if they decide they want they are using diatonic pitch collections. In the images below, I have constructed a series of triads using only the notes that exist in the pitch collection of G major, starting on each note of the scale. Triads are just three-note chords, hence the prefix ‘tri.’ The letter names are in the noteheads, with the chord names are presented above on the staff.

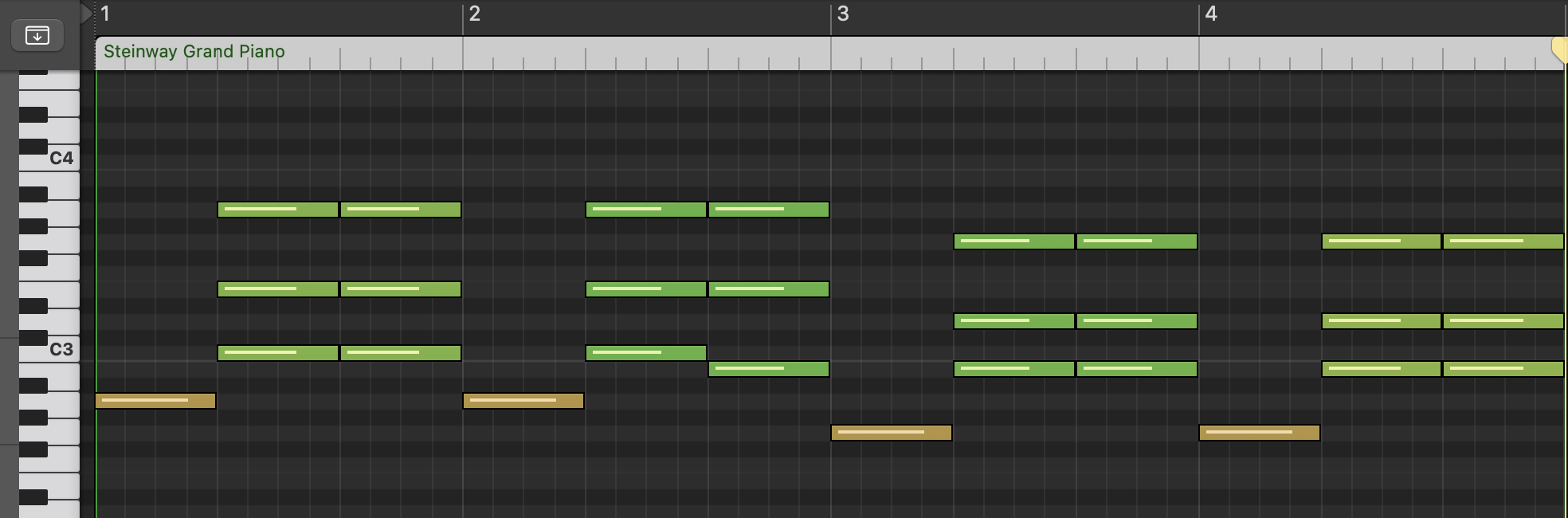

The same series of chords as seen on a piano roll.

The name of the chord is derived by the note name it is built on followed by the quality of the chord. These are considered “pop chord symbols,” and just like scales can have different modal qualities, so too can chords. The first chord here, ‘G,’ is a major chord. For one reason or another, a chord name with just the letter name is considered by default to be major. This means that the chords of ‘C’ and ‘D’ in this collection are also major.

Chords with a lower case ‘m’ next to them are minor in quality. So ‘Am,’ ‘Bm,’ and ‘Em’ are all minor in quality. When reading these symbols, you would say “A minor” or “B minor.” Listen to each of these chords below, switching back and forth between them.

As you’re listening to these, you should notice distinct aural differences. The major chords all sound different from one another, but also sound similar in a different way. This is especially evident when compared to the minor chords which also sound similar to one another in a way, but are distinct in their sound when compared to the major chords. If you agree, then congrats! You’ve just completed your first comparative analysis of music. It may not seem like much now, but it’s the first step to more critical listening of your favorite music.

You should have noticed one chord I didn’t even bring up. It’s a funky one that isn’t used too much in mainstream pop music, though it is used every now and then, especially when moving tonalities. That is the diminished chord, and at least one will appear in every diatonic pitch collection. You can listen to it here, and feel free to compare it to the major and minor chords.

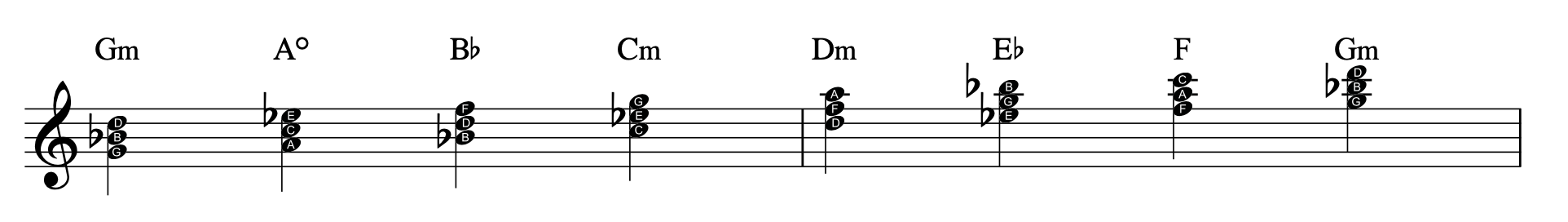

The same process of creating triads within a pitch collection can be done with the minor mode as well, which repositions the chords along the scale as seen below. In any case, the single largest reason for creating chords inside a pitch collection is to establish tonality for a piece of music. Just like the individual pitches have certain functions within a key, so too do the chords. In pop music, the common relationships between chords allow us to begin building a song proper through the use of chord progressions. We’ll dive into these in the next module, but for now, we need to move on to our last component, meter.

Identifying Meter

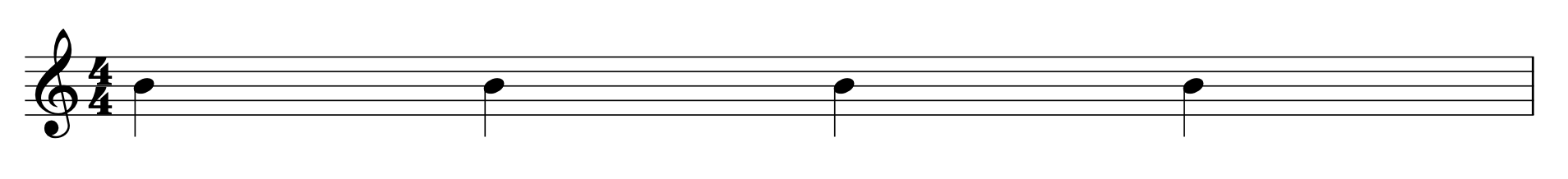

Defining meter is simultaneously simple and nuanced. In simple terms, meter is how you tap your foot along to or dance in time with a song. In more complicated terms, meter is how we perceive and organize the strong and weak beats of a song. Beats are defined in terms of tempo, which is a measurement of beats per minute, or BPM. In western music, whether traditional or DAW notation, beats are organized into measures and are subdivided further from there. Measures are simply used as a way to organize our music within the meter.

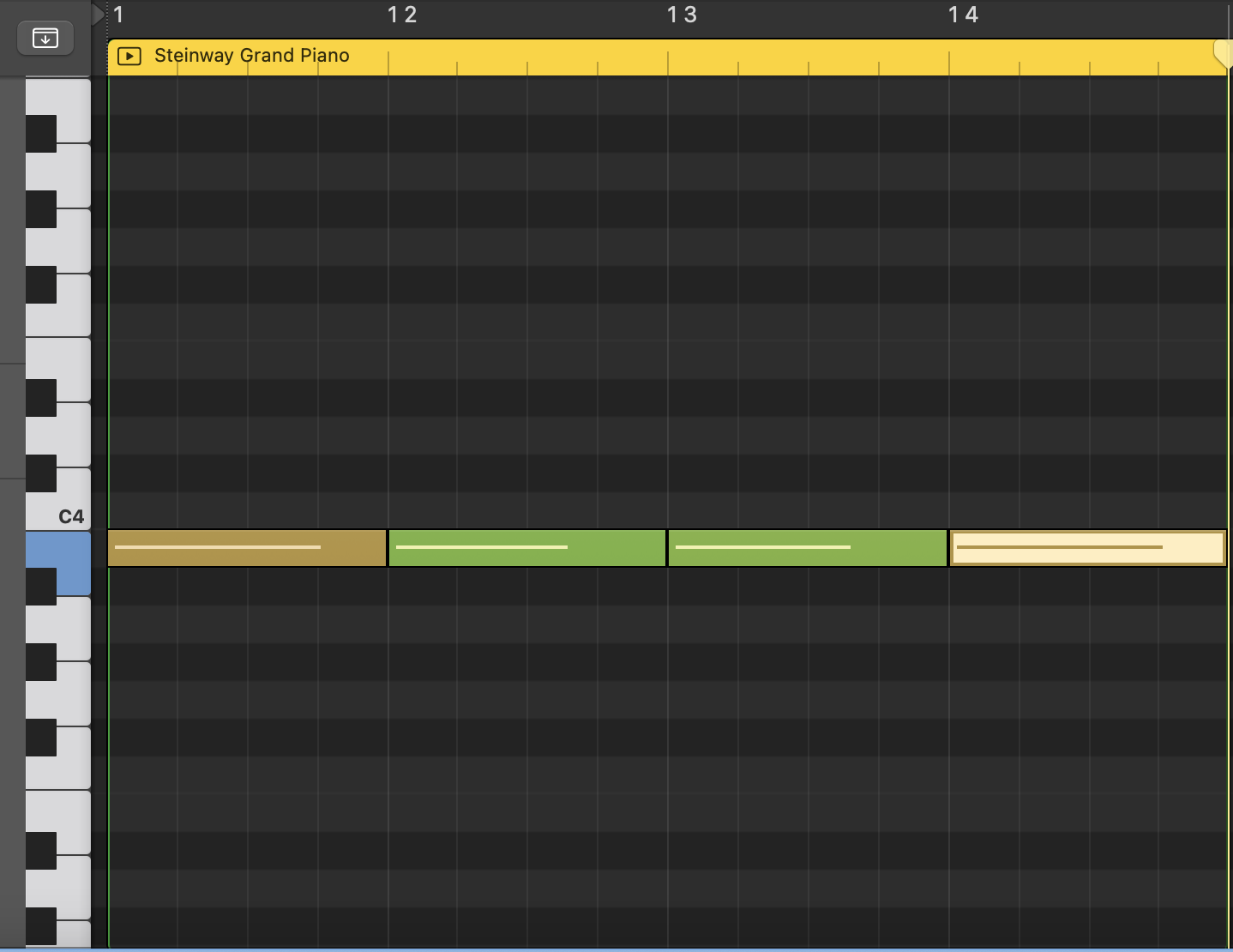

Let’s look into this by starting with the images to the right. In both images, we have four notes that are evenly spaced from one another. This shows the basic division of by far the most common meter, 4/4 (as seen in the time signature, the two numbers on the left side of the staff.). 4/4 meter means there are 4 beats per measure, just like you can hear in this audio file.

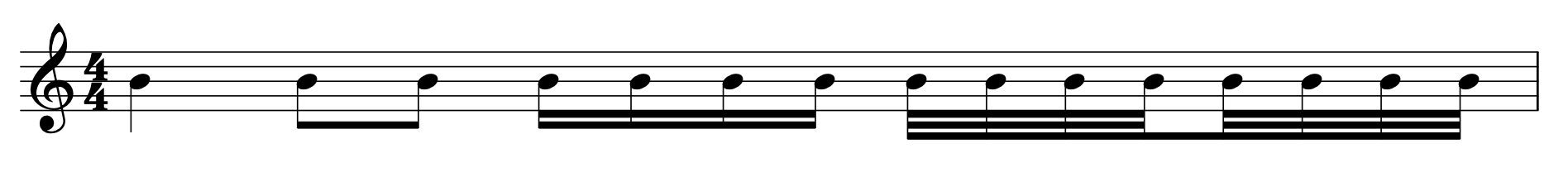

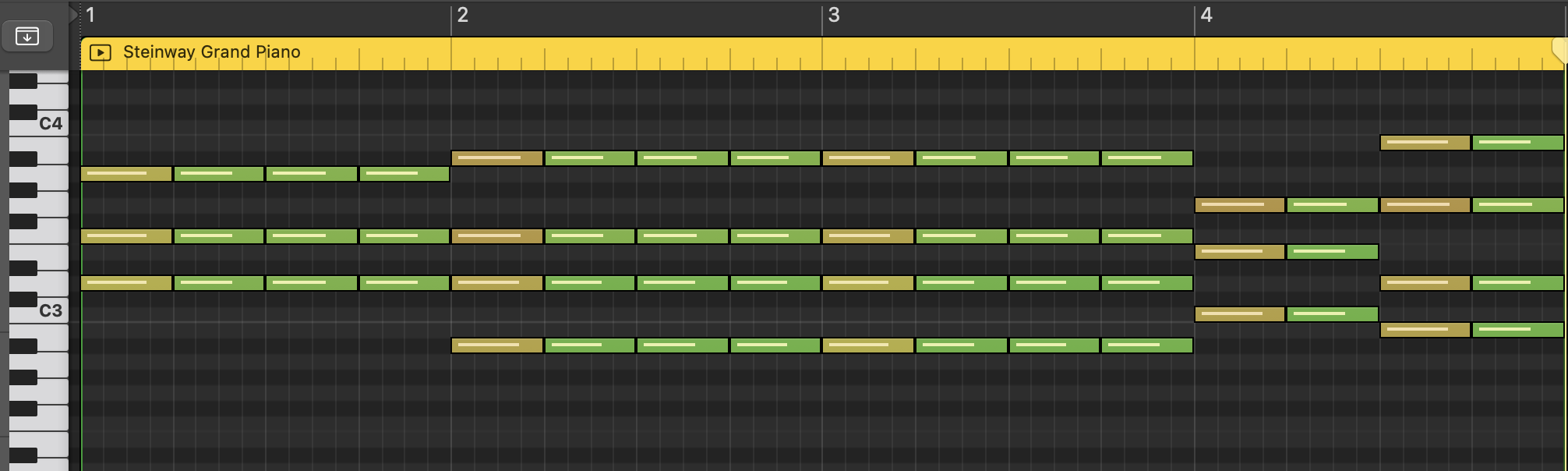

Let's demonstrate meter in a way that is more intuitive and musically realistic. I’ve created two small, very simple snippets of music. The first example is in 3/4, where I play chords on every beat while putting extra emphasis on the first beat of each measure. As you can see in each measure, either in the written notation or the piano roll, there are four measures filled with three beats of music each. Across this phrase, the chord changes once, starting on the third measure. In this example, the meter is completely supported by the quarter note rhythms, the emphasis of the first beat of each measure, and further solidified in the chord change happening on the first beat of the measure.

Listen to this example again and tap along or move to the music. Try counting 1, 2, 3 - restarting the count on each measure. You should find yourself being able to keep up with the music, and you will have consciously identified the meter of a piece of music!

In these images to the left, we have those same four beats, which are sub-divided across each beat. The first beat is comprised of a quarter note, the second beat is comprised of 2 eighth notes, the third beat is comprised of 4 sixteenth notes, and the fourth beat is made up of 8 thirty-second notes. These different notes are used in different combinations to create rhythms. You can think of rhythms as the forefront musical content in a song, and meter as the background, or backbeat that holds everything together.

Now that is a stupid amount of numbers to try and keep track of. Luckily for us, music is rarely this annoying. This simply shows you how beats can be divided and how they are organized across a measure of music. These divisions are also not exclusive to the 4/4 meter, but extend to all others as well, another common one being 3/4 in modern pop - that is 3 beats per measure, instead of four.

While it is common for chords to change at the start of each measure, it doesn’t necessarily have to. Chords can be prolonged in the middle of the phrase or change mid-measure just as you can see in this example. The meter is still heavily emphasized in this case with quarter note rhythms and emphases on the first beat of each measure.

Again, tap or move to the music, instead this time you will count to 4 before restarting. Despite both of these examples consisting of quarter note rhythms, they have different feelings. The 3/4 may feel easier to dance or move to, like a waltz. Whereas the 4/4 is easy to tap out and bob your head with, you certainly have to change the way you move to it if dancing. If you are able to discern this, you’ve been able to internalize the meter! Congrats!

The idea of meter is so ingrained in our culture that it barely needs an explanation. However, laying this theoretical groundwork will allow us to identify music that subverts our metric observations, as we will see in Module 6. For now, however, let’s get into some real examples of music to make a stronger connection to these components and how they work together.

So we know how these components are built, but how do we hear them?

Well, you practice the identification of them through listening. When listening to a song, we can easily identify components such as meter and tonality. If you’ve got a bit of experience and know what to listen for, you may be able to pick up some more nuanced components as well, such as instrumentation. Let’s dive in with our first song.

200 Copas by Karol G

200 Copas is a 2021 music chart-topper by Colombian singer Karol G. She is a young artist who has been consistently been releasing hits in the Latin trap and reggaeton circles. Listen to the song at least once to familiarize yourself with it. While listening, I want you to move or tap along to the music, just as I asked before. While feeling this way, critically listen and determine what meter is being used. As a hint, it will either be the 3/4 or 4/4 feeling we covered earlier.

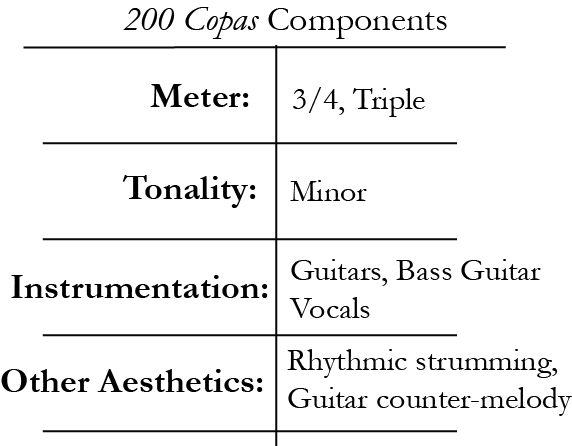

Did you figure it out? You should have determined that the song has a 3/4 feeling. If you’ve got a really good ear, you will have noticed that the 3/4 example I made earlier mimics the beginning of the verses in Karol G’s song - in both meter and chords. The identification of the meter shouldn’t have been too tricky. Though if you did have trouble, don’t worry too much. There are a lot of factors in this piece that may make it difficult to identify this meter.

The first factor making meter identification difficult is relatively small instrumentation, featuring only guitars, bass guitar, and Karol G’s vocalization. Despite no explicit percussion instrument, the song is able to have a strong sense of meter through the accented beats in the guitars and the interactions of stressed and unstressed syllables in the singing. The second factor making meter identification difficult would be the rhythmic patterns. Unlike the simple quarter note rhythms you heard earlier, this song features sixteenth note strumming patterns and variations in the vocal rhythms. As I referenced earlier, these rhythms do align with and support the meter, but can quickly overwhelm the ear if you’re unfamiliar with the song.

To the right, you’ll see a chart I made up for this song to draft its components. I only asked you to identify the meter for this piece, but let’s see if we can expand our process of identification in the next piece to include tonality, instrumentation, and other aesthetic elements as well!

Keep an Eye on Dan by ABBA

Keep an Eye on Dan is another 2021 song by the Swedish pop group ABBA. The group has been a worldwide phenomenon since the 1970s and has recently begun releasing music again. We’re going to do the same listening exercise again. This time in addition to meter, see if you can’t figure out the tonality of the song. It will either be in the major or minor mode. If you think you’ve got the hang of it, figure out what is the instrumentation is - as in what instruments are used in the song. And if you’re up for a real challenge, subjectively describe the main aesthetics of the piece - are there any notable rhythmic patterns or interactions between instruments, things that make the song distinct? Give it a shot!

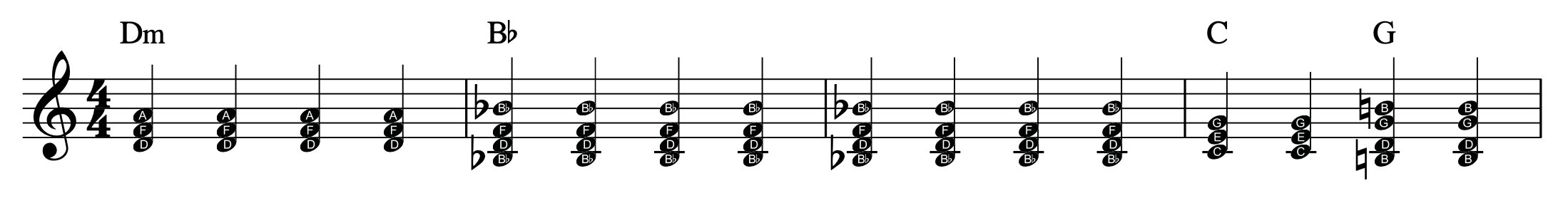

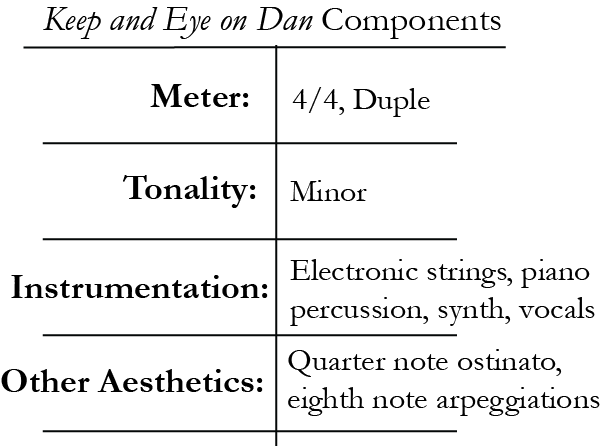

How did you do on this one? Check out the chart to the right and compare your notes. You may have noticed that I used the chorus of this song in the 4/4 example earlier. In a way, the meter of this song is easy to identify since it is mostly quarter note rhythms in the piano/synthesizer. On the other hand, there isn’t a great difference in the emphasis of beats, which can cause some confusion. As for tonality, the piece is squarely in the minor mode. You may have heard the song being in a major mode during the chorus of the song and that is no accident. Oftentimes songs will move to different modes temporarily in order to provide contrast with the rest of the piece.

As for instrumentation, the piece features mostly electronic instruments, including electronic drums, strings, piano, and synthesizers. The most notable characteristics I picked up were the quarter note ostinatos and eighth-note arpeggios that persist throughout most of the piece. An ostinato is a repeated, unchanging figure that serves as a background component in a piece of music. In this piece, the ostinato is the piano notes that start at the very beginning of the song and barely change. An arpeggio is a chord that is broken up across multiple rhythms and beats, as heard in the synthesizer parts for Keep and Eye on Dan.

Maybe you heard this as well but didn’t have the words to describe it. If you felt a little lost in finding the aesthetics of the song, that’s okay too! We’re going to continue to practice this as we continue on in the course. With each module complete, you should feel a little more comfortable in describing music in your own terms!

Learning Extension: Non-Western Melodic Construction

Earlier I briefly mentioned that a world outside of the western pitch hierarchy exists. Unfortunately, I have little education or experience outside of western music. Fortunately, I’m not the only musician or teacher to exist. Check out this video by Anuja Kamat where she compares western musical components in terms of classical Indian music theory. Don’t fret if you’re not familiar with all the terms and concepts she’s throwing around - keep with it and you should be able to begin making connections with your current understanding of music and theory.

Unfortunately, Anuja is no longer producing videos regularly, but if you find this video interesting, you should definitely check out the rest of her catalog.

Module Assignment 3

Component Identification: Last Day on Earth

Listen to Last Day on Earth by beabadoobee. Once you have, complete this identification quiz that will ask you about the components we talked about in the previous 2 songs of this module.

(Click the ‘Module Assignment’ link for a quick way to the assignment)