Module 7

Advanced Meter; In The Context of Nu-Metal, Prog Rock, and Hyper-Pop

Evanescence, Caroline Polachek by Crack, tricot by Avex Entertainment

More sub-genre labels…

I mentioned in the previous lesson how pedantic it can be to define different pieces of music considering how diverse artists are getting in their personal styles. When I was choosing music for this module, all of the pieces used for demonstration included some form of progressive techniques or technologies that aren’t always found in the broader, more popular genres we talked about in previous modules, including but not limited to complex metric styles. And, in full disclosure, this allowed me to pick from some of my absolute favorite artists. So, using the diversity of these genres as a pretense, we’re going to complete some advanced meter analyses of some of my favorite pieces!

A distinction: meter vs. time signature

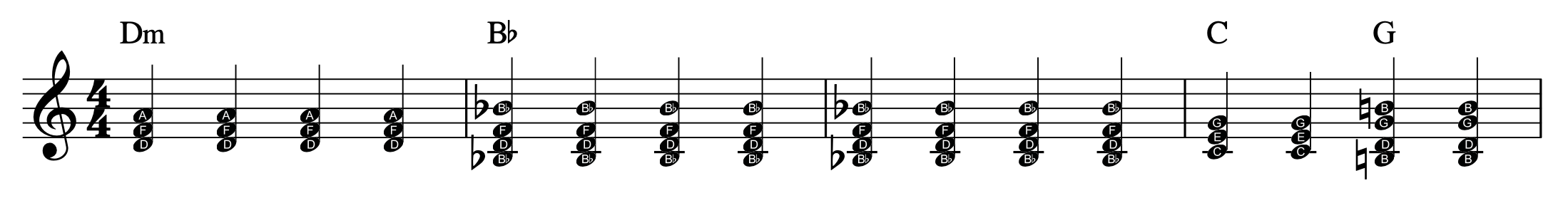

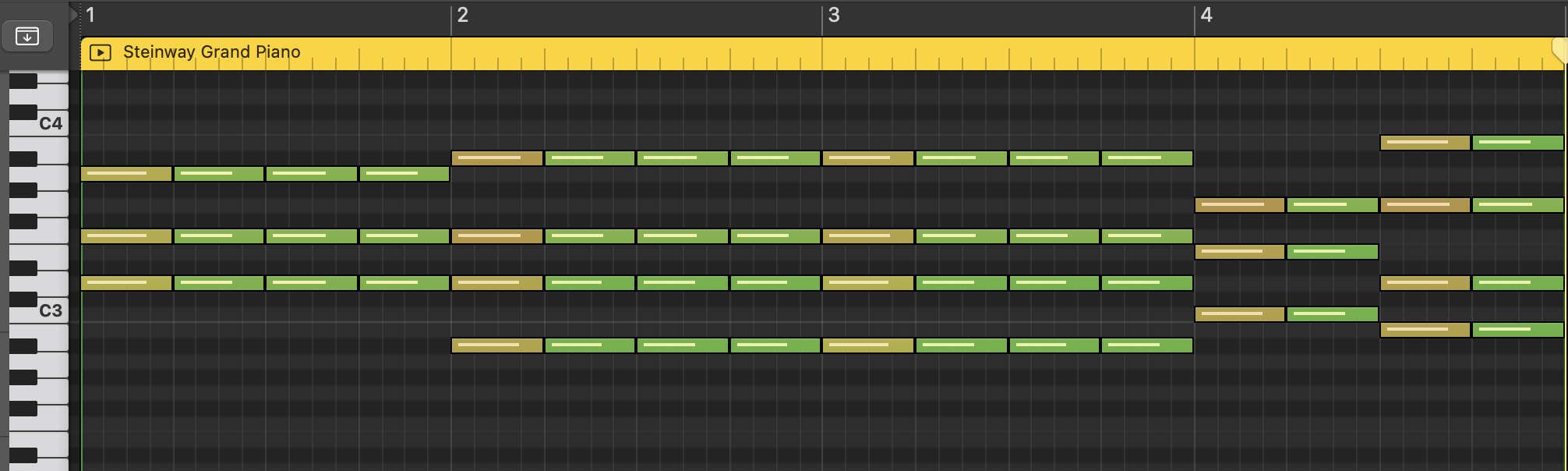

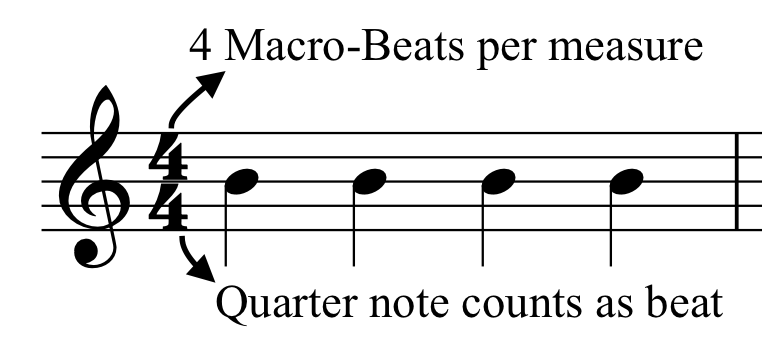

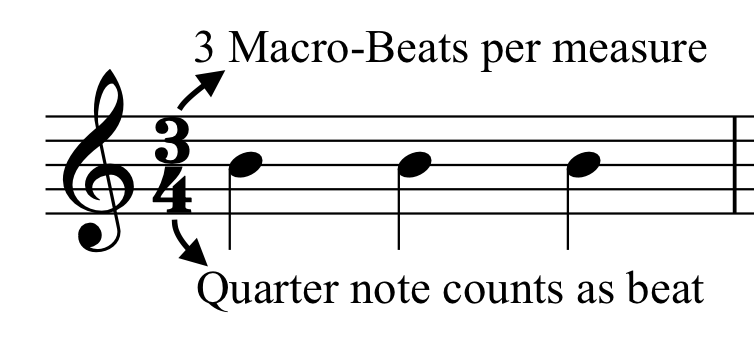

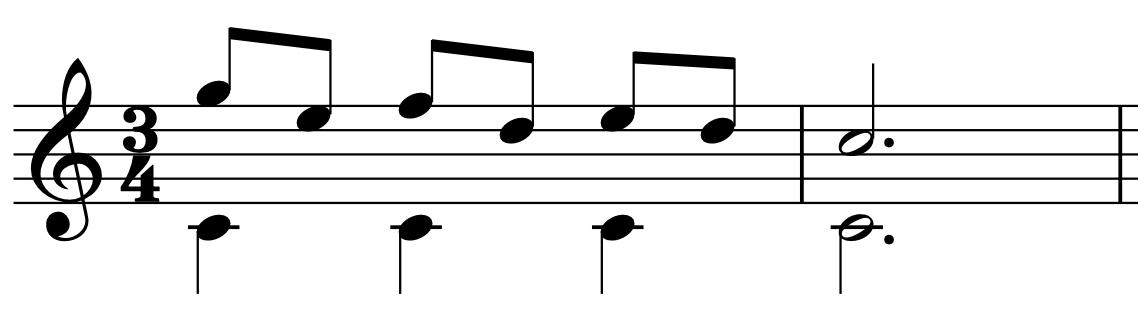

Let’s start with a bit of review of what meter is and define some important terms. As a plain descriptor, meter is the collective grouping of accented and unaccented beats across measures of music. Meter is often consistent throughout a piece, and provides a regular rhythmic expectation that we can play, dance, or move to. However, as we will soon see, the breaking of metric expectation is also used as a musical device in some pieces. Back in Module 3, we looked at two very common meters in commercial music today, 4/4 and 3/4. In both examples, the meter was most defined by a strong (accented) downbeat of each measure followed by several unaccented beats. See the examples below again.

The yellow shaded notes on the DAW represent a higher velocity, thus a more accented sound.

Meanwhile, the lighter green notes represent a lower velocity, thus a softer sound.

When taken in totality, the accented and unaccented notes create common meters that we can move along to. This necessitates a distinction between what we call meter and time signatures. Time signatures, as seen at the beginning of the staff in the traditional notation above, simply tell us how many notes are organized into each measure. While they can imply meter, they do not necessitate it. For example, a piece of music can have two completely different metric feels despite sharing the same time signature. When dealing with songs with a 4/4 based meter, these differences may seem subtle, and the meter is often informed by other elements or instrumentation in the music. Listen to just the beginning of both of these songs you should be familiar with now. Consider how you feel time, and think about in what ways the two songs’ meter differ.

While the beginning of Keep An Eye On Dan is clearly heard in 4/4, it hardly has any metric emphasis to orient us even when it comes to downbeats! What we do get though are chord changes and the addition of new instrumental phrases that in effect provide some emphasis on the first beat of each measure. Though, the overall effect provides an ametric feel, ametric meaning lacking meter.

Meanwhile, Forgotten Souls sets up its metric emphasis with both the drumset and guitar. The drumset’s snare provides strong accents on beats 2 and 4 with a heavy bass accent on the downbeat of each measure - as we understand is nominal for rock songs. While not as prominent, the guitar part that starts in the first verse mimics these strong “2 and 4” accents in a technique called slap strumming. By muting or quieting the strings and slapping the strings, the guitar creates a sort of percussive effect in the spaces it isn’t letting notes ring out.

Tangential techniques aside, this is at least one example where two songs in 4/4 have different metric feels. This extends to any and all time signatures and metric feels, which are often mixed, matched, and modified to create new musical gestures in all kinds of music.

Some more theory

Now that you can feel and have a better grasp on some of these metric nuances, let’s introduce some common units that help us build and analyze time and meter. We’ll first be defining time signatures and what macro and micro beats are, and then we will be organizing them into the categories of simple, compound, odd. Keep in mind that what I’m about to present is language and terms that I have used in previous classes that students have had success with. Others may use different terms to describe the very same ideas, so don’t think about these terms as definitive definitions. Remember, descriptive > prescriptive.

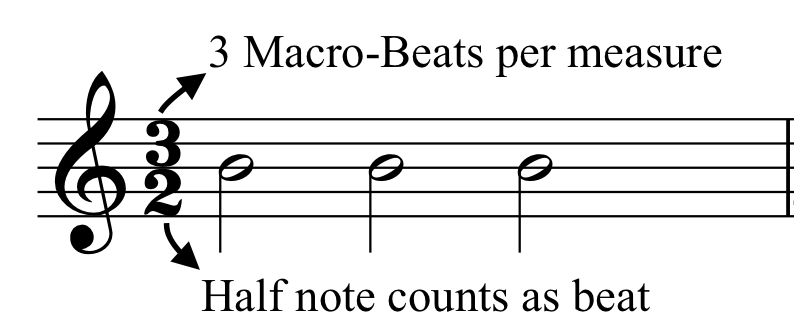

Macro-beats are essentially what we have been trying to identify when listening to the songs in this module and from Module 3 - the beat that you tap along to. In some of the most common time signatures, the macro-beat is a quarter note or a dotted quarter note. Hold on to that question for now, as there will be more on dotted notes in a bit.

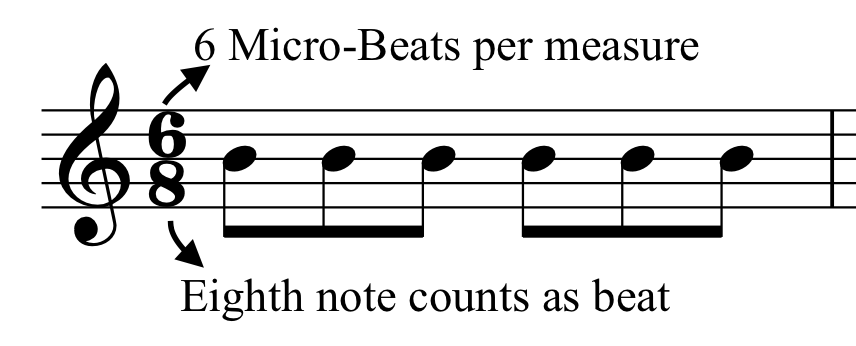

Micro-beats, as the name suggests, are the smaller divisions of the macro-beat in a given time signature. Micro-beats aren’t necessarily analyzed outside of purely theoretical exercises but may be seen as the rhythmic ideas that help define the meter. However, I mostly use the term micro-beats to help better explain simple, compound, and odd-meter.

The two numbers of a time signature tell us the makeup of each measure. Depending on the kind meter the time signature is representing, the bottom number tells us what note comprises the macro-beat and micro-beat, and the top number tells us how many beats make up a single measure.

Simple-meter refers to a meter whose macro-beats are divided evenly into two micro-beats. The bottom number of a simple-meter time signature tells us which note gets the macro-beat. Examples of simple-meter are often found in the 3/4 and 4/4 time signatures. In 4/4, the macro-beat unit is the quarter note, and there are 4 quarter notes in each measure. In 3/4, the quarter note still is the macro-beat and there are 3 quarter notes per measure. Another example would be 3/2, where the half note (as determined by the 2 in the time signature) is the macro-beat, and there are 3 half notes that make up a measure.

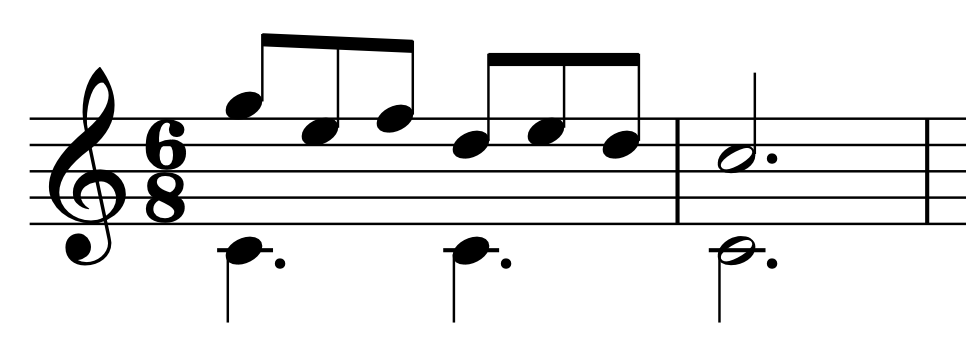

Compound-meter refers to a meter whose macro-beats are divided evenly into three micro-beats. However, and this is where it gets tricky, the bottom note tells us which note is the micro-beat. The top number then tells us how many micro beats make up a measure. By grouping micro-beats into groups of three, we can find the macro-beat unit. A common compound-meter is 6/8, where the 8th note is the micro-beat, and there are six micro-beats per measure. If we take these micro-beats into groups of three, we also see the macro-beat is the dotted quarter note. As you can see now, the dotted quarter is just the value of 3 eighth notes - a dot adds half of the value of the original note. Dotted notes are always going to be the macro-beat unit of any compound meter.

This creates a “triplet feel” as 3 micro-units comprise the macro-beat, instead of the 2 that we’re used to. Let’s take a listen to a couple of examples. The first example on the left is emphasizing a simple meter, while the example on the right is emphasizing a compound meter. Despite both examples having the same number of notes or rhythmic values, they both have distinct metric feels. These meters are best represented with the time signatures of 3/4 and 6/8 respectively, and can’t really be interchanged.

The movement from a compound meter to a simple meter (and vice versa) is a relatively common musical technique that is employed when moving between sections to create a new feeling. This is called metric modulation. Additionally, an underlying simple or compound meter may have a specific instrument play outside of the meter, sort of establishing two meters at once. This is the foundation on which the rhythmic idea of polyrhythms is built. We’ll see a couple of real examples of these techniques soon.

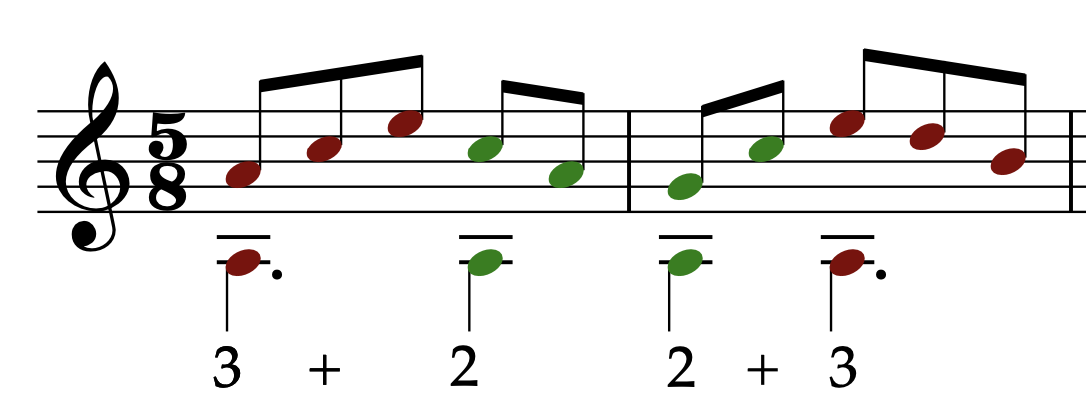

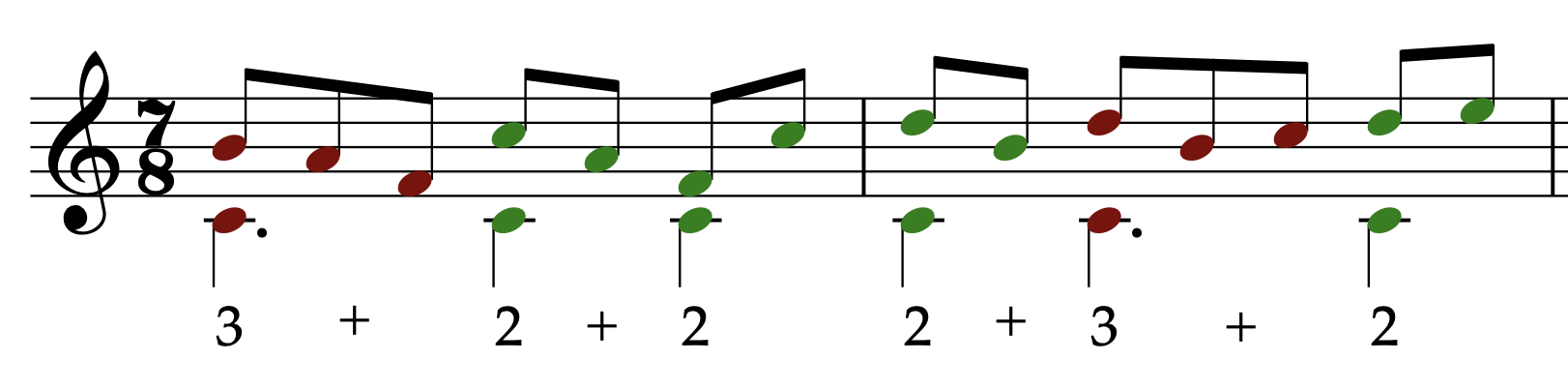

Odd-meter refers to a meter that mixes both compound and simple-macro beat units. Some common odd-meter time signatures include 5/8, 7/8, and 8/8. Each measure of these time signatures includes 5, 7, and 8 eighth notes respectively. An interesting feature of odd meters is that the metric emphasis can easily be changed by just moving around where the compound and simple beats are placed. See the examples to the right here where the groups of 3 are labeled and shaded red, while the groups of 2 are shaded green. These meters are inherently unbalanced and can be hard to follow, especially with how ingrained even meters are in modern pop music. However, while they lack a certain balance, you will soon realize that these kinds of meters can create a kind of regular groove that is easy to follow along with by virtue of repeating and reinforcing said metric patterns.

Now you might be wondering why a signature of 8/8 would be considered an odd meter. Well, despite using the term “odd,” not all odd meters contain an odd number of micro-beats. Looking at an 8/8 example, one may be inclined to visualize and hear it as 4/4. But if you are mixing compound and simple beats, it is clearer to represent the meter with a time signature of 8/8. This is where the distinction between meter and time signatures comes into play again. One song that features an 8/8 odd metric emphasis is Clocks by Coldplay - listen below. Though, for all intents and purposes, this example could be easily read and understood if notated as 4/4.

The piano is emphasizing the meter by striking the top note of each arpeggio a bit harder than the other notes. The drumset further defines this meter with its kick drum. Remember the groups of 3 are considered compound beats, and the groups of 2 are considered simple.

Moving on

For a very clean overview and review of these new terms and ideas, you can check out this lesson from MusicTheory.net. Otherwise, let’s get into some actual examples of specific rhythm and meter techniques. I’ve included YouTube videos for each example, so you can better navigate the song’s timeline as you’re listening. I also want you to keep in mind that while I’m showing you western written notation, it’s not always clear whether or not the artists use the same system. That is to say, many of these rhythmic ideas and nuances are cultivated outside of sheet music, but I’m providing it post-hoc just to provide visualization. Anyways, let’s get into it.

Broken Pieces Shine by Evanescence

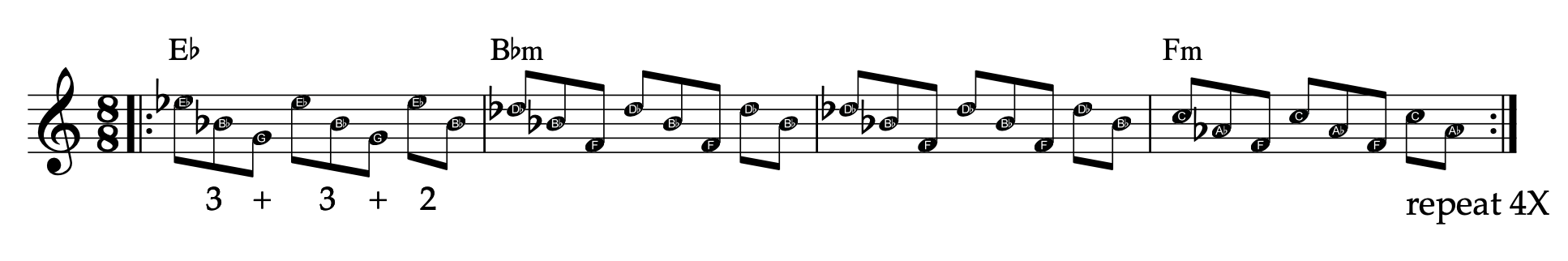

In the previous module, we discussed how nu-metal, and by extension metal in general, is a derivative of rock. Straight-forward rhythmic ideas with a strong metric emphasis on beats 2 and 4 (when in 4/4). However, metal and nu-metal are progressive genres by definition, and this extends to metric and rhythmic play. This song by Evanescense is pretty tame compared to the progressive ideas seen by some other artists, but it provides us a good starting point to look at a few, more subtle, rhythmic techniques that spice up our listening. Give it a listen, and then we’ll identify some new terms!

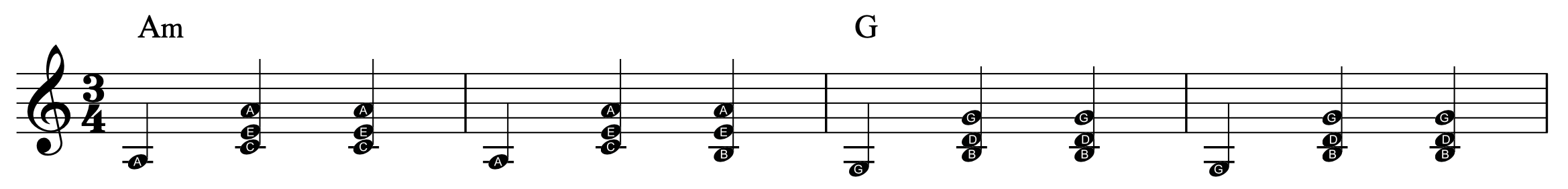

Syncopation is a rhythmic technique that momentarily emphasizes a different rhythmic or metric gesture outside of the established meter. Syncopation is used expertly several times in this piece to accentuate transitions between sections, mostly dispensed with the vocals. The first example is at the very beginning of the choruses. Look at the example I’ve drafted up here. You can practice following along to the music, or simply keep up with lyrics. Listen to this section again and see how Amy Lee anticipates her entrance to the chorus by delivering “I’m alive” a bit early. If we were wanting to square everything up, the second syllable of “alive” would fall directly on the down-beat as I’ve noted. In my opinion, this early delivery in combination with the late entrance of the other instruments provides space for the vocals to stand out amongst the band at a key lyric. Though, there are many explanations one could derive from this specific decision - the most probable being that it spices up the flow of the song. Even more, syncopation happens in the song’s outro starting at 2:52. Jump to that section and see what you can find.

This song also features our first example of polyrhythms - well, at least of this module. It happens throughout the piece, but it is easily heard in the outro shortly after the aforementioned syncopation. Here, Amy and Jen Majura perform compound macro-beat figures over the simple 2/2 meter. You can see I’ve transcribed the figure to the right. In a way, this polyrhythm figure can be heard as “squeezing in” 3 quarter notes in the space of 2, creating a very common device in simple meters called the triplet. Listen along to this section again while following the music. You can also tap out this specific rhythmic pattern to practice it yourself, and you can easily feel the bounciness to this figure compared to the steady macro-beat underlying it. The triplet is such a common trope across all music, that it hardly stands out as an event in this case. In fact, now that you’ve analyzed it in this way, you’ll likely be able to point it out in your every day listening.

So Hot You’re Hurting My Feelings by Caroline Polachek

Hyper-pop as we know it has had a cultural explosion in the past few years that has sort-of brought the genre and its aesthetic close to the mainstream. In its purest form, hyper-pop is a derivative of pop music that contains over-produced (heavily processed) music and vocals, as well as purely digital instrumental accompaniment. General aesthetics of the genre range from laid-back lounge beats to more up-tempo pop songs. In more recent years, hyper-pop has taken these core techniques and aesthetics and pushed them to their extremes. This is most evidently seen with groups like 100 gecs, where their vocals are processed beyond the normal human timbre and the digital instruments are degraded to the point of total distortion. We’re going to take a step back from this hardcore digicore and look at a more traditional hyper-pop piece by U.S.-based singer, Caroline Polachek.

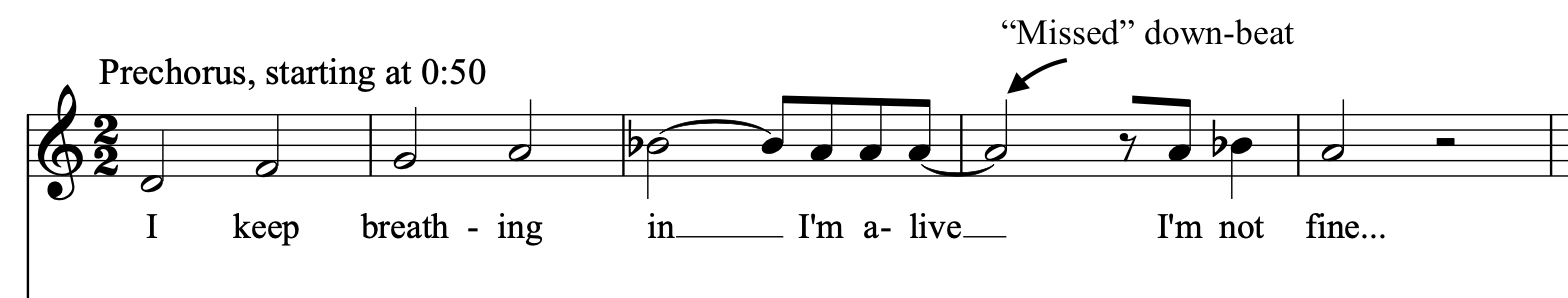

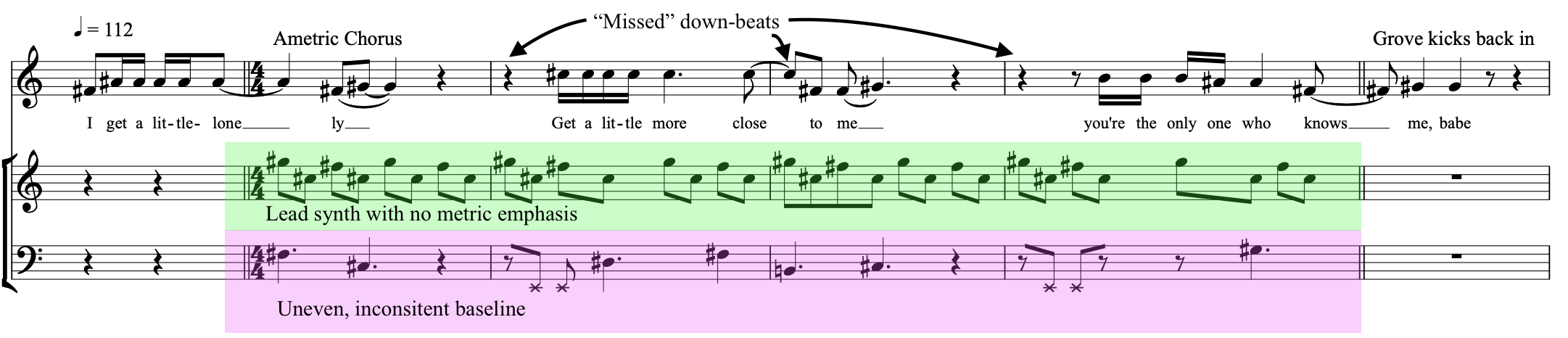

As for rhythmic or metric material to analyze, we will be looking to the chorus of this piece, first happening at 0:54. More specifically, I want to note the ametric content of the chorus, which takes us completely out of time and meter. Remember, I defined ametric music as music that has no perceivable meter. Ametricism is used in a ton of progressive and avant-garde music, and you even hear it to some extent in pop songs, such as with music videos that have an ametric opening or outro. I think Caroline brilliantly toes the line between complete ametricism and beat-oriented groves.

See the example of music I’ve traced out below here. The synth-lead is highlighted in green, and the bass is highlighted in purple. When added all together, the notes and rhythms fit neatly into 4 measures of 4/4. However, that traditional pop-rock metric emphasis is completely gone. The vocals are floating around at seemingly random rhythmic intervals, the lead synth provides no real rhythmic emphasis, and the bass line is also emphasizing random beats and off-beats. This in combination with getting back into the grove just moments later provides a really nice contrasting aesthetic when compared to the rest of the song. Additionally, this freedom supports the intimate lyrics sung at the beginning of the choruses - perhaps another justification for this musical decision. In any case, I won’t make you squint at this for too long. Let’s move on to our last piece of the module.

Dogs and Ducks by tricot

Our last song for today is brought to you by another personal favorite of mine, tricot. We talked a little about prog-rock in the previous module and how the term progressive is used to describe more advanced or experimental techniques in music-making. A quite niche derivative of the genre is found in math-rock. Math-rock, as the name suggests, heavily employs uncommon meters or combines 2 different meters into longer groves. tricot has been described as a math-rock band for a while, though it seems that the band tries to avoid definitive labels for their music.

But what do we mean by uncommon meters and what do they feel/sound like? Let’s try to answer this question with a bit of a challenge. Listen to the song here, Dogs and Ducks by the band. As you are listening, try tapping along to the beat and find the meter. No need to transcribe it or figure out what a time signature is - just try to keep the beat. The phrases throughout the song are regular and repeated, so you should begin to find some parts to hang onto and reorient yourself as you’re listening.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

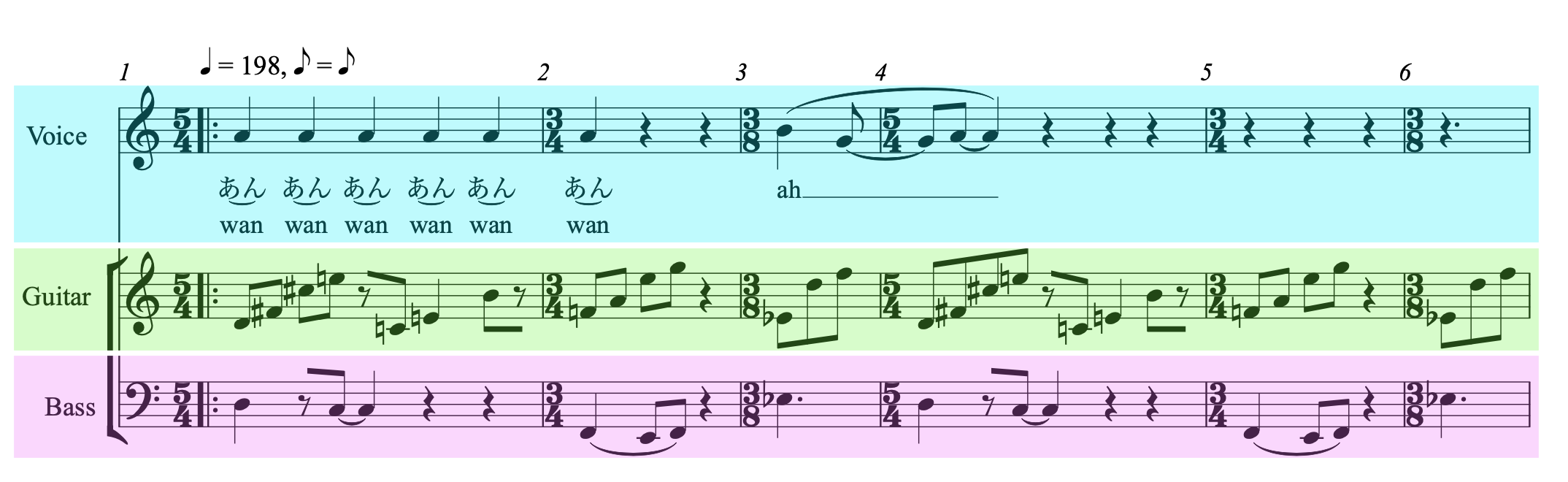

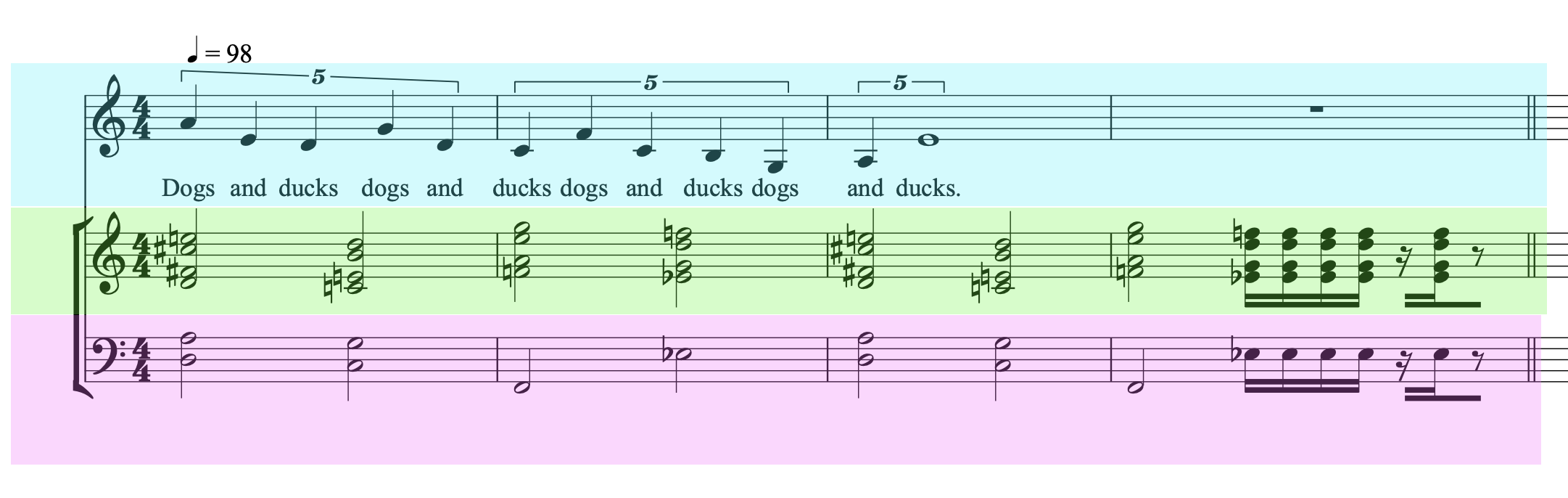

How did you do? We’re you able to keep up, or did you find yourself kind of tripping at some moments? If you were tripping over yourself, there’s a very good reason. The quarter note beat may seem easy to find or tap out to yourself as the phrases pass, but you will always find yourself out of phase when listening to the first section and its counterparts throughout the song. Let’s take a look at a transcription I made of the intro that repeats for the first and see what’s going on. Again, to guide your eyes I’ve shaded the vocals in blue, the guitar in green, and the bass in purple.

Fun fact: “wan-wan” seems to be the onomatopoeia word for a dog’s bark in Japanese, like woof or bow-wow in English.

Okay, so there’s a lot going on here. Let me take you through my rationale in making this measure by measure to see what’s happening. I’ve notated the first measure in 5/4, which is best outlined with the 5 quarter notes sung by the vocalists. I then used the last “わん” as the downbeat of the following 3/4 measure, which consists of 3 quarter note beats best emphasized by the guitar and bass. We then come to the last measure, which consists of only 1 compound beat - a complete left turn compared to all of the preceding simple beats. This last measure almost feels like an accident, and can almost be felt as such. Think about tapping out 8 simple quarter-note beats, followed by a 9th beat that’s just a little bit longer. This very long-winded explanation of the notation is exactly why it may have felt like you were “tripping” in your listening. Practice these phrases again while listening, and see if you can keep up better.

This kind of metric nonsense is referred to as composite meter or composite time signatures. Composite meters and signatures combine or add multiple kinds of meters together into a regular phrase or grove that is often repeated. The repetition associated with these kinds of meters creates a sort of macro-groove that allows us to easily keep up with the song once we’ve heard it a couple of times.

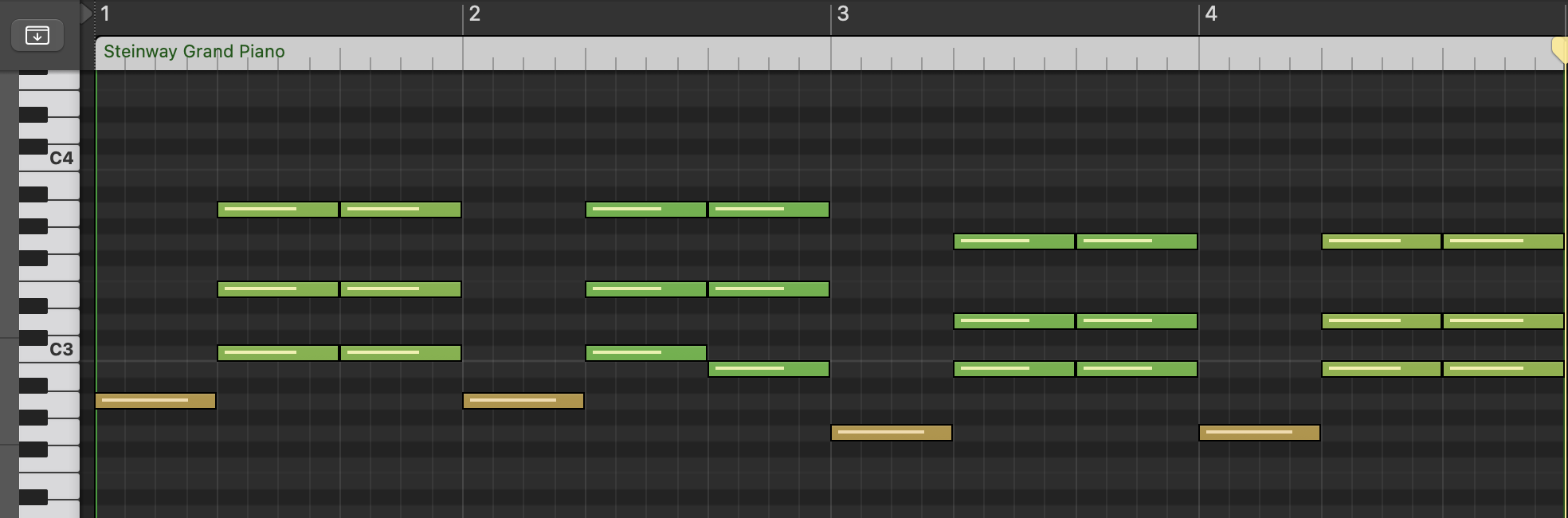

Let’s take a look at one final component that’s key to this song, metric modulation. I mentioned earlier that metric modulation takes place when moving between simple to compound meters and vice versa. This is true, but metric modulation can really happen between any kind of metric grooves, including composite meters. You will have heard this quite clearly as we move from the first section to the chorus - a transcribed version can be seen to the right here.

In this case, we not only get a clear metric modulation to the 4/4 traditional rock feel but also a new polyrhythm! The 4/4 grove is outlined by the guitars and bass with their half-note rhythms and is further emphasized by the drumkit. Meanwhile, Ikkyu Nakajima provides a distinct 5-note polyrhythm over the 4/4 measures, which serves to emphasize the start of each measure and provide further metric ambiguity in the spaces between the background vocals and instruments. This polyrhythm is called a quintuple and can be expressed as 5:4 - that is, 5 quarter notes equally fitted into the space of 4).

If you continue to hang around music like this, you are sure to pick up much more rhythmic and metric nuance, guaranteed! For now, however, let’s get take a look at a couple of assignments in relation to advanced meter.

Learning Extension: Extra Credit Assignment

Radiohead is an older, English prog-rock and electronic band. Their 2004 song Everything In Its Right Place is a great summation of their overall style and aesthetic. Additionally, it features some neat metric and rhythmic tricks that you don’t hear all that often. As part of an extra credit assignment worth 20 points (+2% of your final grade) I want you to figure out a few things for me about the song, and use some of the ideas you will have learned in this module to justify your decisions. You can use the guided listening assignment as a sort of guide as to what I want you to look for, though I promise it’s not nearly as complicated.

Click the hyperlink above to be taken directly to the assignment on BlackBoard.

Module Assignment 7

Advanced Metric and Formal Listening

Listen to the song Story 2 by clipping., and focus on how meter and time is handled throughout the piece. Try tapping along to any beat you find, or move to the music in some way. Keep listening to the piece while you complete this guided listening assignment on Blackboard.

(Click the ‘Module Assignment’ link for a quick way to the assignment)